La crise rencontre la crise

L’état de la pauvreté au Canada évolue rapidement. Selon les dernières données disponibles, la pauvreté et l’insécurité alimentaire sont en hausse et augmentent rapidement. Selon la plus récente Enquête canadienne sur le revenu, un Canadien sur dix vit dans la pauvreté et près du quart (23 %) de la population est en situation d’insécurité alimentaire. Ces données correspondent à ce que nous avons constaté en première ligne dans les banques alimentaires. Avant la pandémie, les banques alimentaires canadiennes comptaient en moyenne 1 million de visites par mois. Cette année, les banques alimentaires ont vu les visites mensuelles grimper à plus de 2 millions Les banques alimentaires ont atteint 1 million de visites en 25 ans d’existence. Ce chiffre a presque doublé en l’espace de 5 ans seulement. La demande a atteint un point critique. Jamais autant de personnes n’ont eu recours aux banques alimentaires dans l’histoire du Canada.

La hausse de fréquentation des banques alimentaires dénote une réalité économique considérablement modifiée. Entre 2015 et 2020, le Canada a connu le déclin de la pauvreté le plus spectaculaire et le plus complet jamais enregistré. Un Canadien sur 7 (14,5 %) vivait sous le seuil de pauvreté en 2015. Cinq ans plus tard, ce chiffre est tombé à 6,4 %, soit moins de la moitié de l’ancien taux et une baisse d’environ 56 %.

Cependant, en 2022, soit seulement deux ans après que le taux de pauvreté du pays ait atteint son plus bas niveau historique, la tendance a commencé à s’inverser. Le taux de pauvreté a augmenté de 10 % dans la population canadienne entre 2020 et 2022, réduisant de moitié les progrès réalisés depuis 2015. Par ailleurs, l’insécurité alimentaire – un des indicateurs des difficultés économiques – a augmenté de manière significative depuis 2021, année pendant laquelle 15,7 % de la population était concernée. En 2024, l’insécurité alimentaire a explosé en touchant près du quart des Canadiens, soit près de 9 millions de personnes dont 2 millions d’enfants. Un certain nombre de raisons expliquent cette hausse alarmante :

- La hausse rapide des taux d’intérêt et le durcissement des conditions financières pour lutter contre des taux d’inflation élevés depuis des décennies.

- Un manque de logements à l’échelle du pays, en particulier de logements à prix abordables.

- La perte de mesures de soutien du revenu comme la PCU et d’autres mesures ponctuelles que le gouvernement fédéral et le gouvernement provincial avaient instaurées pour compenser à court terme à la fois les effets de la pandémie et ceux de la crise inflationniste subséquente a entraîné une diminution globale du revenu disponible pour beaucoup de familles, en particulier celles à faible revenu.

- En raison du ralentissement de l’activité économique et d’une hausse (lente) du taux de chômage, la pression exercée poussant à offrir des salaires plus élevés et à poursuivre les progrès réalisés vers un marché du travail plus inclusif a été réduite.

- La croissance démographique importante et rapide sans infrastructure sociale nécessaire pour absorber un tel afflux.

Ces facteurs combinés ont créé un changement dans le paysage économique. En effet, le coût des produits essentiels comme la nourriture et le logement a dépassé la croissance des salaires. En conséquence, nous devrions nous attendre à ce que les taux de pauvreté continuent d’augmenter à mesure que de nouvelles données seront disponibles dans les mois et années à venir. Cela signifie qu’il y aura plus de personnes âgées en difficulté, plus d’enfants en situation d’insécurité alimentaire et plus de personnes partout au Canada craignant de ne pas arriver à joindre les deux bouts.

On constate que cette pauvreté croissante ne vient pas du manque d’effort des personnes à faible revenu au Canada. Pour les deux quintiles de revenu les plus bas, le coût des produits essentiels comme la nourriture, le logement et le transport occupe la majorité du budget des ménages. Des millions de Canadiens consacrent maintenant la totalité de leur revenu voire plus aux besoins essentiels et doivent encore assumer d’autres coûts fixes comme les factures d’Internet et de téléphone, le remboursement des dettes et la garde d’enfants. Cela laisse d es millions de foyers sans aucunes économies ni coussin de sécurité financière. Ils ont peu de possibilités d’améliorer leur situation puisqu’ils doivent se concentrer sur leur survie.

Une réponse inadéquate

Les détails décrits dans la section précédente ne sont une surprise pour personne au gouvernement.

En réponse à la crise actuelle croissante, le gouvernement a mis en place plusieurs mesures indispensables pour aider à lutter contre certains des problèmes susmentionnés. Par exemple, ils se sont engagés à construire plus de logements, à augmenter les objectifs d’immigration, à investir dans les transports publics, dans l’internet à haute vitesse et dans la garde d’enfants. Malheureusement, les répercussions de ces programmes et de la plupart des autres mesures gouvernementales ne se feront pas sentir avant de nombreuses années. Nous ne saisissons pas encore à quel point ces changements aideront, mais nous savons qu’ils n’aideront pas les personnes qui éprouvent des difficultés aujourd’hui.

Malgré si le pire de l’inflation semble être derrière nous, le prix des aliments (entre autres coûts) devrait demeurer élevé tout au long de 2024 et au-delà. La pression financière exercée sur de nombreux ménages a atteint un point critique, car les besoins essentiels mobilisent l’essentiel de leur revenu voire la totalité. De plus en plus de gens sautent des repas, s’endettent et perdent petit à petit leur dignité. Les Canadiens sont les plus endettés des pays du G7[1], et on s’attend à ce que la situation se détériore.

Les récents efforts visant à stimuler la concurrence dans le secteur de l’épicerie sont utiles pour favoriser la modération des prix, mais il est peu probable qu’ils entraînent une baisse de prix suffisante pour répondre aux besoins des personnes à faible revenu.

Même lorsque le chômage était à son plus bas niveau historique ou presque après la pandémie, les revenus se sont avérés insuffisants. Par exemple, il existe un écart d’environ 8,50 $ l’heure entre le revenu nécessaire pour assumer les frais de base et le salaire minimum offert en Ontario. L’effet de cet écart est clairement visible dans les banques alimentaires. En 2023, alors que le pays enregistrait un taux de chômage élevé, les banques alimentaires ont reçu un taux de demandes sans précédent. Compte tenu de la hausse du chômage et du resserrement du marché du travail, nous pouvons nous attendre à ce que ces conditions s’aggravent.

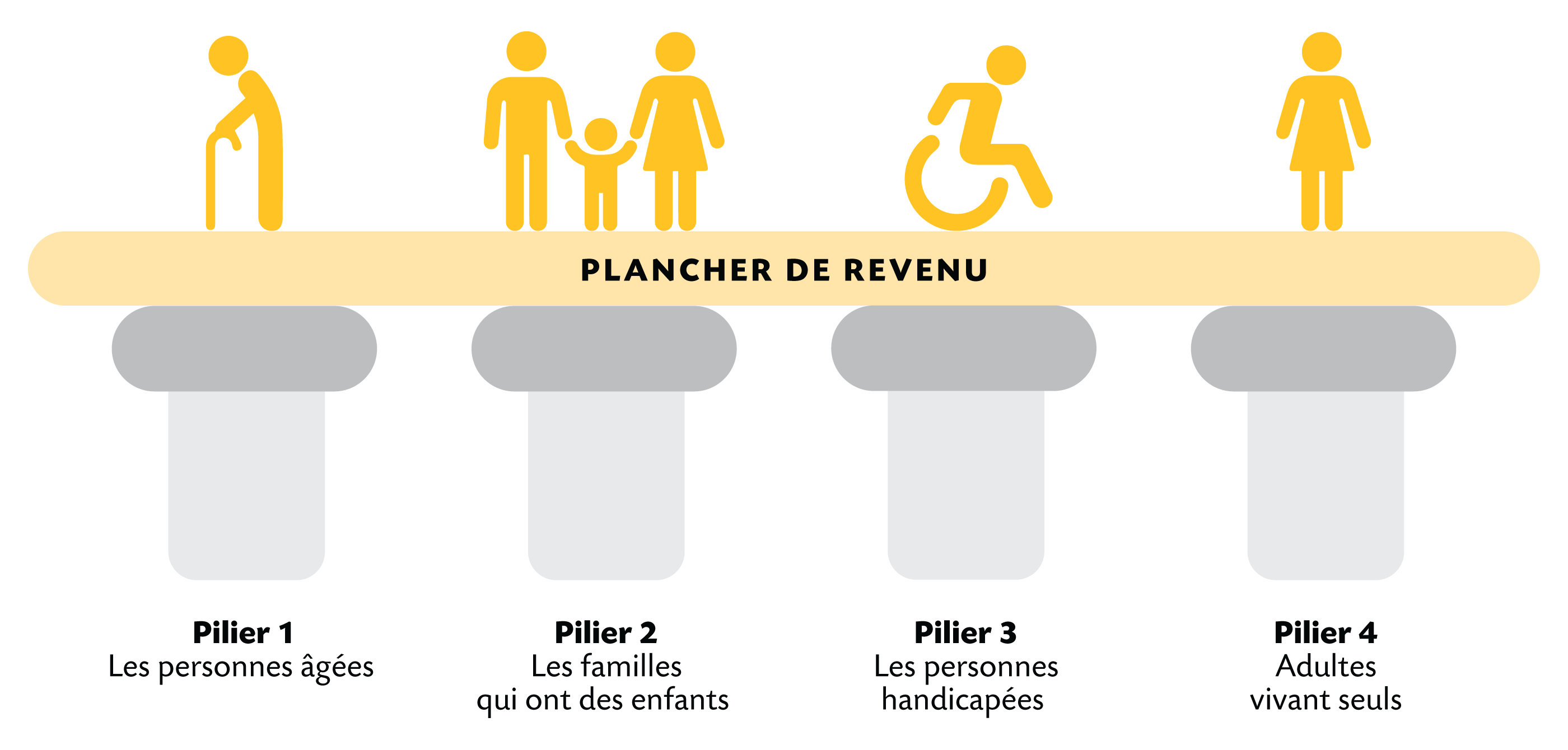

Tandis que les gouvernements cherchent des solutions, ils doivent prendre en compte les stratégies précédemment utilisées dans le passé pour réduire la pauvreté. Des recherches approfondies montrent que les versements de transferts constituent la politique la plus efficace pour réduire la pauvreté. Selon des estimations récentes, l’ACE a permis de réduire l’insécurité alimentaire d’environ 5 % (et potentiellement jusqu’à 9 %), tandis que la PCU a été un facteur essentiel à la forte diminution de la pauvreté en 2021[2][3]. De la même manière, le supplément de revenu garanti et la sécurité de la vieillesse réduisent de manière efficace la pauvreté chez les personnes âgées à faible revenu. Malheureusement, les programmes de soutien financier n’ont pas suffi dans les dernières années; les enfants et les personnages âgées continuent de représenter un pourcentage croissant parmi les personnes ayant besoin des banques alimentaires au Canada. Les gouvernements doivent s’assurer que les programmes suivent l’augmentation du coût de la vie s’ils veulent que ceux-ci soient efficaces.