Constantly worrying about where your next meal is coming from can be an incredibly stressful experience.

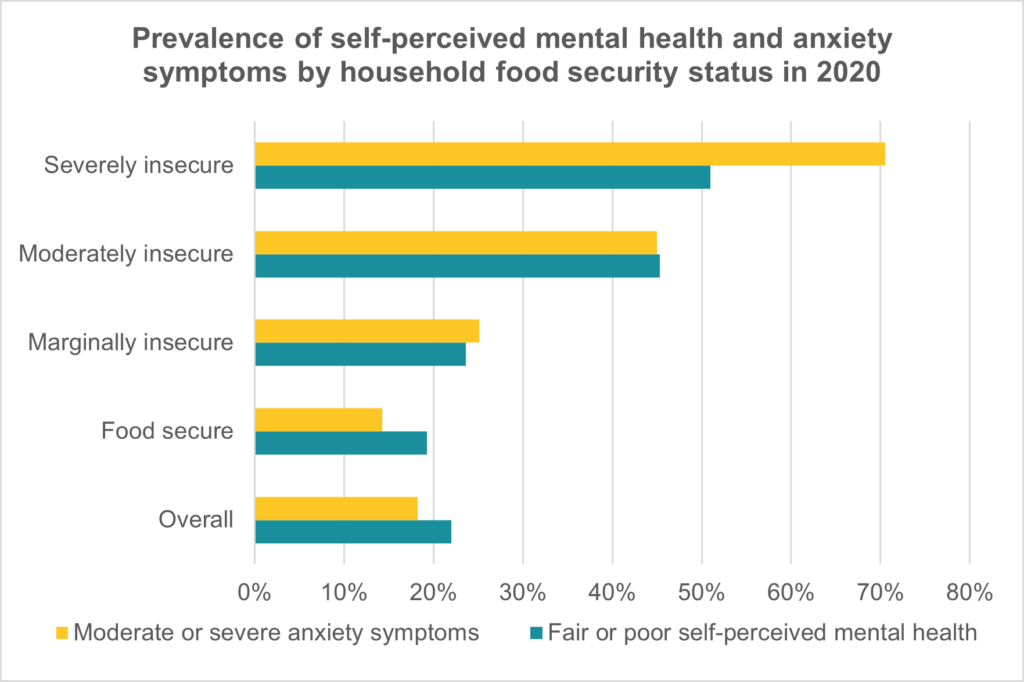

According to a Statistics Canada report on food insecurity and mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic, Canadians living in severely food-insecure households were seven times more likely to report symptoms of moderate or severe anxiety compared to households that were food secure.

Certain population groups were more likely to be food insecure, such as lone-parent households, individuals who rely on government assistance as their main source of income, and individuals who rent their home.

As mentioned in our HungerCount 2021 report, single-person households that are food insecure experience higher levels of mental health issues than other households.

Many people in this situation have mental health issues that go untreated because they lack supports, are stuck in a cycle of inadequate social assistance or disability-related supports, or have lost a job and have nowhere to turn for new training and education.

Food banks see the mental health impacts of food insecurity every day, which is why the Petawawa Pantry in Southern Ontario teamed up with Mental Health Services of Renfrew County (MHSRC) to better support clients during a mental health crisis and ensure they have access to basic necessities, such as food and personal care products, in the form of “crisis boxes.”

Laurie Alton, the President and Co-Founder of The Petawawa Pantry Food Bank who also works for MHSRC, said the project was inspired by a new collaborative approach to addressing hunger in the community.

“Throughout 2020 and 2021, the food bank mobilized its community outreach program which offers a delivery service for individuals who are ill, disabled or struggling with mental health issues, and as part of this we reached out to 25 social service agencies and organizations that serve Petawawa,” Alton said.

A connection was made with the region’s Mental Health Services Mobile Crisis Team, which works with residents who find themselves unhoused or insecurely housed, Alton continued. Further discussions led to the creation of a list of items that clients would need and from there, the project began to take shape.

In 2021, a total of 695 crisis boxes were prepared and delivered to those in need, including nearly $7,000 worth of grocery gift cards.

“With many mental health medications, you cannot take them on an empty stomach,” Alton said. “Having food at your disposal takes down the stress of taking medication, and it certainly puts people at ease and helps with anxiety.

“We are so linked—our mind, our body. People need food and when they have it, they are able to focus, their moods are improved, and they can interact with their peers in a better way.”

Molly Fulton, a clinical manager at MHSRC responsible for staff distributing the crisis boxes to clients, added that the positive impacts of the project have been obvious in the people they serve.

“Food security is such a crucial staple to anyone’s wellbeing and mental health, and being able to provide someone in need with food and hygiene products helps to ease such a major concern,” Fulton said. “Crisis workers who are providing frontline support to individuals in the community have all commented on what a wonderful concept this initiative has been.

“The feedback from the clients has been nothing but positive and appreciative.”